Hillside Cemetery, aptly named for its winding gravel driveways, lush hillocks, and mature cypress trees, was founded in 1808.

Formerly located upon the land of Josiah Wolcott, one of Farmington Township’s first settlers, what is now known as Hillside Cemetery came into existence in 1808 following the death of Mary “Polly” Wolcott, Josiah’s 18 year old daughter. Remaining within the Wolcott family for over 40 years, the cemetery was transferred to the trustees of Farmington Township in 1853 by Orlando Wolcott, one of Josiah’s grandsons.

By the end of the Civil War, the original cemetery, which ran parallel to State Route 88 (Greenville Road), was expanded outwards; eventually encompassing 19 acres in all. In 1865, a marble obelisk dedicated to West Farmington’s Civil War dead was erected in the new section of the cemetery. Raised at the cost of $1,400, it was paid for by the citizens of West Farmington and dedicated by future president James A. Garfield, then a congressman. At present, Hillside Cemetery is West Farmington’s main burial ground, and is still in active use, although the old section has been closed to new interments.

ALL ORDERS FROM A DISTANCE THANKFULLY RECEIVED: THE SIGNED HEADSTONE OF CLARISSIA HOLLY

While this series is predominantly focused on those buried beneath the headstones in Trumbull County’s historic cemeteries, occasionally we turn our attention to the lives of those who created the headstones themselves. Often leaving no identifying marks behind, aside from intricate designs that with a keen eye can be ascribed to a particular carver or workshop, occasionally these mystery craftsmen left us a clue as to who they were by signing their work. One local headstone carver with a penchant for signing his work was Thomas Jones of Cleveland; who around 1838, carved the headstone of young West Farmington resident Clarissa Holly.

A native of Clyro, Wales, born in 1793, Thomas Jones arrived in the United States on August 24th, 1833 in Philadelphia aboard the ship “Cottingham.” Making his way to Cleveland, it would be only a year after arrival on February 1st, 1834 that an advertisement was placed in the Cleveland Advertiser for his services as a carver located on Seneca Street near Erie Street Cemetery. Specializing in marblework, apparently Jones was more than happy to provide his wares to those living outside of Cleveland, as evidenced not only by Clarissia’s stone in Hillside, but in an early advertisement stating “all orders from a distance (are) thankfully received.” Initially carving solo, signing his stones “T. Jones, Cleveland,” in 1843, Jones’ entered a partnership with his three sons, Thomas Jr, William, and James, becoming known as T. Jones and Sons,” or in some advertisements, the Cleveland Marble Factory. Gradually entering the market of ornamental sculpture in addition to headstones, the firm’s most important commission was the base for the former Oliver Hazard Perry statue on Public Square in Cleveland, now located at the Perry International Peace Monument in Put-in-Bay.

WEST FARMINGTON’S FIRST DEATH: MARY “POLLY” WOLCOTT

During the early days of Trumbull County’s settlement, death could often come in unsuspecting ways: falling tree limbs, kicking horses, and unattained fires all severed hardy pioneers from their mortal coil. Such an unseemly accident is what would claim the life of Mary “Polly” Wolcott, West Farmington’s first death and Hillside Cemetery’s first burial. The fourth of seven children born to Capt. Josiah Israel and Lydia (Russell) Wolcott, Mary, or Polly as she was called, was born on October 1st, 1789, in Wethersfield, Hartford County, Connecticut. While little is known regarding her life before migrating to Ohio, it is known that according to church records Polly was baptized on November 15th, 1789, at Rocky Hill, Connecticut by family pastor Rev. John Lewis. Following her father’s purchase of land in West Farmington, or as the township was called up until 1817, “Henshaw,” Polly came westward with him and the rest of the family, walking most of the way.

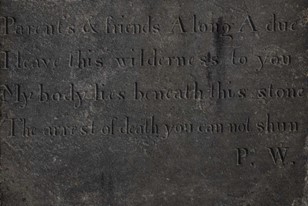

At some point during the journey, while crossing a stream, she took a fall from a log––soaking herself. From this incident, she developed a cold which turned into tuberculosis. Despite the best efforts of her half-brother, a physician, Polly succumbed to her illness on September 2nd, 1808. After “a few trees were felled, and a grave was dug” upon the family property, Polly Wolcott was laid away in the dense wilderness that was then West Farmington. At some point following her demise, likely whenever suitable carving talent arrived in the area, a headstone was erected for her. Made from mudstone, it is relatively simplistic in nature, featuring three-six sided stars and all capital, serif text on the inscription. Somewhat irregularly written, Polly’s epitaph refers to the wilderness that was once surrounded her grave: Parents & friends A long A due/I leave this wilderness to you/my body lies beneath this stone/The arrest of death you cannot shun”

“A BRAVE AND BELOVED COMRADE:” HOMER H. STULL

Out of the multiple conflicts America has endured throughout her history, perhaps none have had the impact on Trumbull County as the Civil War did. From 1861 to 1865, over 4,300 soldiers and sailors enlisted in the Union cause from all 24 townships countywide. Among those men was Homer H. Stull of West Farmington. The youngest of three children born to James and Catherine McIllves, former natives of New York, Homer Stull was born in Liberty Township in 1828, but as a young boy, moved to West Farmington with his family.

As of the 1860 census, he resided in Warren in the household of his brother, John, a prominent lawyer and is listed in occupation as being a “miner.” On September 10, 1861, just five months into the Civil War, Homer H. Stull, aged 33 years old, enlisted with the 14th Ohio Independent Light Battery of Cleveland as first lieutenant. Colloquially known as “Burrow’s Battery” after commander Jerome Burrows, the 14th Ohio predominantly saw service in Tennessee, but Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia as well.

While stationed in Jackson, Tennessee in early May 1863, Homer H. Stull came down with “bilious fever,” an outdated term for diseases such as malaria, typhoid, typhus, or hepatitis. On May 17th, 1863, Stull passed away at age 35 years old in the service of his country. Taken back to West Farmington and interred at Hillside Cemetery underneath a grandiose marble obelisk bearing the motif of an eagle clutching a shield with numerous furled flags behind, the epitaph inscribed upon a scroll beneath the main carving notes the monument was “erected by the members of the 14th in honor of memory of a brave and beloved comrade,”

">

">