Explore Brookfield Center Cemetery - Trumbull County’s historic burial ground dating back to 1809, where early Ohio settlers still speak through stone.

The original section of Brookfield Center Cemetery on a chilly November day (Photo by the author).

Just beyond the south end of the Brookfield Village Green, at the corner of State Route 7 and 82, sits what is now known as Brookfield Center Cemetery. Used as an informal burial ground as early as 1809, it was not formally established until 1812, when Samuel Hinckley, a native of Northampton, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, who had purchased Brookfield Township from the Connecticut Land Company in 1799, formally deeded one acre of land at the far northern end of the present cemetery for $1.00.

Hinckley had only one stipulation—that the cemetery and the nearby village green be preserved for public use forever. Still in use as a public cemetery, it has expanded and evolved over the past 212 years to serve the growing needs of Brookfield Township. Despite these changes, the original section remains, holding the stories of Brookfield’s earliest settlers.

Elijah Sikes: A Master of His Trade

The first known stone by Elijah Sikes, that of Hannah Dwight (d. 1792) at the South Cemetery in Belchertown, Hampshire County, Massachusetts. Note the spoon-shaped soul effigy, taken from stones carved by his father, as well as his initials at the bottom: “E.S.” (Photo by the author)

When writing about historic cemeteries, we often focus on those buried beneath the gravestones rather than those who created them. Elijah Sikes is an exception, as he is one of the few gravestone carvers in Northeast Ohio for whom we have detailed records, thanks to his earlier career in New England.

Born in 1772 in Belchertown, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, he was the son of Joseph Sikes, Belchertown’s eminent gravestone carver. Elijah undoubtedly learned the trade from his father and, at just 20 years old in 1792, carved his first stone—the grave marker of Hannah Dwight, buried at South Cemetery.

Initially, he patterned his work after his father’s, featuring ghostly, spoon-shaped “soul effigies”, rosettes, twining vines, and heralds of death, such as the Latin phrase “memento mori” (“remember death”).

A later period l Sikes stone done in the Neoclassical style, dated 1828 from the Neshannock Presbyterian Cemetery in New Wilmington, Lawrence County, Pennsylvania; about as far south as one will find his work. Like the ornate stones found in the Brookfield Center Cemetery, the rosettes, twining leaves, and herald of “REMEMBER DEATH” are all holdovers of when he carved throughout Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Vermont. (Photo by the author).

After marrying Lucretia Anderson on January 10, 1794, in Chester, Massachusetts, Elijah Sikes eventually settled in Lenox before moving to Dorset, Vermont, where he operated a marble quarry and significantly broadened his skills.

During this time, he began experimenting with Neoclassical carving styles, drawing inspiration from local artisans. He adapted “drooping willows” and “pot-shaped” urns, which later became hallmarks of his work.

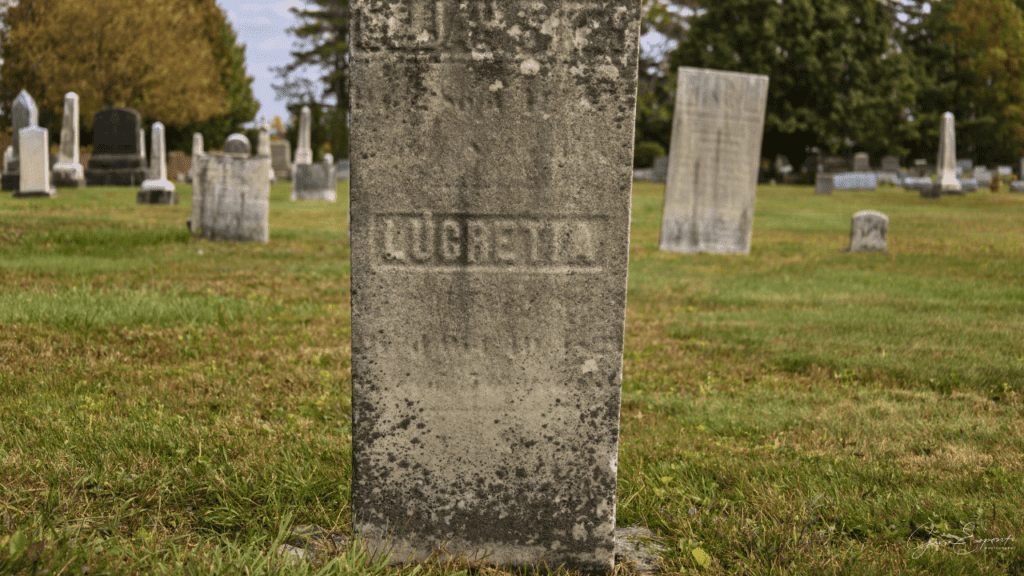

Alas! Such is the irony of life, the unadorned marble tablet of Elijah Sikes, who is buried alongside his wife Lucretia at the Brookfield Center Cemetery, offers little insight into his lifetime as a talented gravestone carver. (Photo by the author)

By 1816, Sikes returned to Norwich (now Huntington), Massachusetts, where he remained until at least 1827–1828, when he moved to Northeast Ohio, settling in Brookfield Township. He continued carving gravestones for bereaved families throughout the region, sometimes creating markers for individuals who had died up to 15 years earlier.

Sikes’ earthly career ended on September 11, 1855, at the age of 83. He was laid to rest at Brookfield Center Cemetery beside his wife, Lucretia. Nearby stand 10 of his original headstones, with an estimated 930 more scattered across Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

Edward Burton: When Blooming Youth Is Snatch’d Away

The beautifully crafted gravestone of Edward Burton was carved by Brookfield resident Elijah Sikes. Note the inscribed verse at the bottom, which begins with “When blooming youth is snatch’d away…”, a line from the 1760 hymn At the Funeral of a Young Person by English hymnodist Anne Steele. (Photo by the author).

The youngest of six children, Edward Burton was born in 1815 in Worthington, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, to Asa II and Eunice Weber Burton. His family is noted as one of the first full families to settle in Brookfield, though the minute details of their lives remain unknown. On January 13, 1828, Edward passed away at just 13 years old.

Interred in the township cemetery established by Samuel Hinckley in 1812, Edward’s grave is marked by a large square brownstone headstone with rounded edges. Carved by Brookfield resident Elijah Sikes, the stone is considered one of his finest works in Northeast Ohio, reflecting the Neoclassical style he mastered in New England.

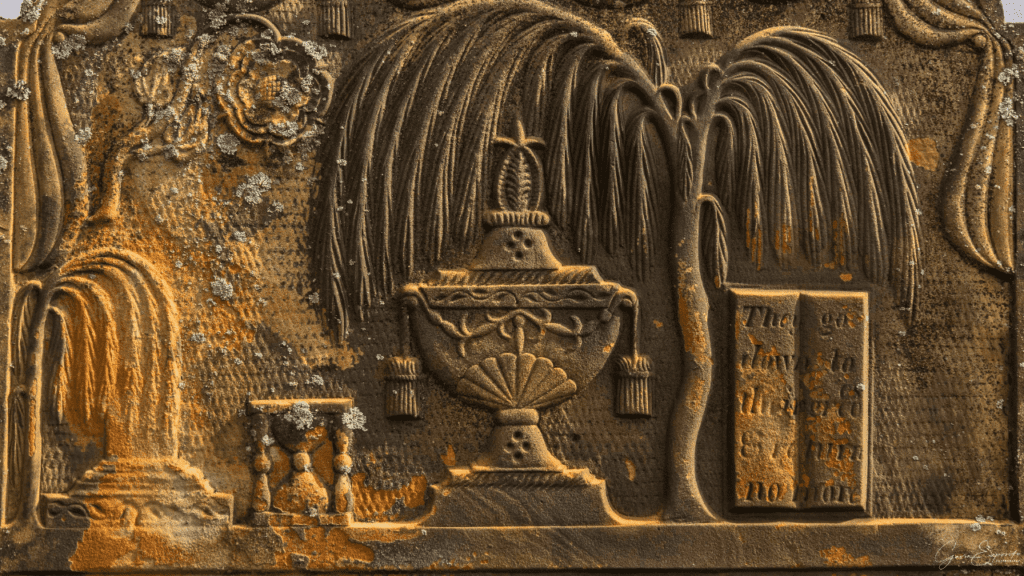

A closeup of the richly decorated top, or tympanum of Edward Burton’s marker, featuring some of Sikes trademarks such as a pot-shaped urn, overarching willow, drapery, rosette, hourglass, and open book. (Photo by the author)

The gravestone is divided into three distinct sections. The top portion, the most ornate, features carved tassels and drapery, a small rosette (one of Sikes’ trademarks), an hourglass, and two weeping willows—one shrouding a broken column, the other an urn—as well as an open book.

The middle section, considerably less intricate, simply bears the common inscription “In memory of…”, followed by Edward’s name, his parents’ names, his date of death, and his age. Visitors to Edward’s beautifully carved monument will notice that he was not the only child of Asa and Eunice to pass away.

A look down at the unique “billboard marker” which commemorates all the deceased Burton children, including Edward. Most common in Maine, this is one of the only of its kind in Trumbull County, if not the Western Reserve. (Photo by the author)

He was preceded in death by his brother Stephen in 1827, followed by William just a month later, Catherine in July of that same year, Charles in 1841, and Eliza in 1854. Unlike Edward, they do not have individual markers but are memorialized alongside him on a horizontal “billboard” stone, a style of gravestone most commonly found in Maine.

John Jones II: Stifled Out By Poison Gas

The imposing granite obelisk of mine superintendent John “Boss” Jones II, who on July 11th, 1877, met a grisly fate along with seven of his men at the Brookfield Coal Company’s mine. (Photo by the author).

Long before the greater Mahoning Valley became a bastion of steelmaking, coal mining reigned supreme. As early as the 1830s, small-scale coal mining operations emerged, primarily in what is now the Brier Hill neighborhood of Youngstown and Mineral Ridge in Wethersfield Township. Mining paused during the Civil War but resumed in the post-war era, with mines rapidly opening in Hubbard, Liberty, Vienna, and Brookfield Townships. By 1867, Trumbull County produced more coal than any other county in Ohio.

A dangerous occupation for many reasons, coal mining frequently led to fatalities, including that of Superintendent John “Boss” Jones II and seven miners of the Brookfield Coal Company, who lost their lives on July 11, 1877. A native of Newcastle Emlyn, Cardiganshire, Wales, John “Boss” Jones II was born on January 21, 1821. Little is known about his early life, but given Wales’ prominence in coal mining, he likely entered the trade as a young man.

Listed on the 1870 census as a “coal digger”, he worked his way up to the position of mine superintendent sometime between then and 1877. On July 11, 1877, Jones and eight of his men were exposed to toxic fumes from a locomotive burning anthracite, or “smokeless” coal. Days earlier, a test using regular coal had proven unsafe, as it filled the mine with smoke. As a result, anthracite was chosen instead. After making three or four trips into the slope to retrieve cars, at around 11 o’clock, the men operating the locomotive suddenly became affected by the gas, collapsing senselessly.

The engineer immediately halted the locomotive and ran the length of the tunnel to raise the alarm. A contingent of men rushed into the mine, but they too were quickly overcome by the fumes. Among the first to die was John Jones, who had taken the role of the “trapper”, a young worker responsible for opening and closing the mine doors. By the end of the day, 36 men had been pulled from the Brookfield Coal Company’s shaft, with six dying before reaching the mine’s entrance, including John Jones. An additional miner, John Young, was retrieved alive but succumbed to his injuries at 6 o’clock that evening, bringing the final death toll to seven.

Initially, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported the disaster as occurring in Wheatland, Pennsylvania, a community four miles southeast of Brookfield. This error stemmed from the “meager telegraphic facilities” along the Erie and Pittsburgh Railway, where news of the incident first surfaced. Although the mistake was later corrected, many newspapers nationwide reprinted the original error, leading to widespread misreporting that placed the tragedy in Wheatland rather than Brookfield. Funeral services were held en masse the following day, July 13, with a vast concourse of people gathering to honor their fallen fellow workers.

Ezra Hart: Who Met A Watery Death

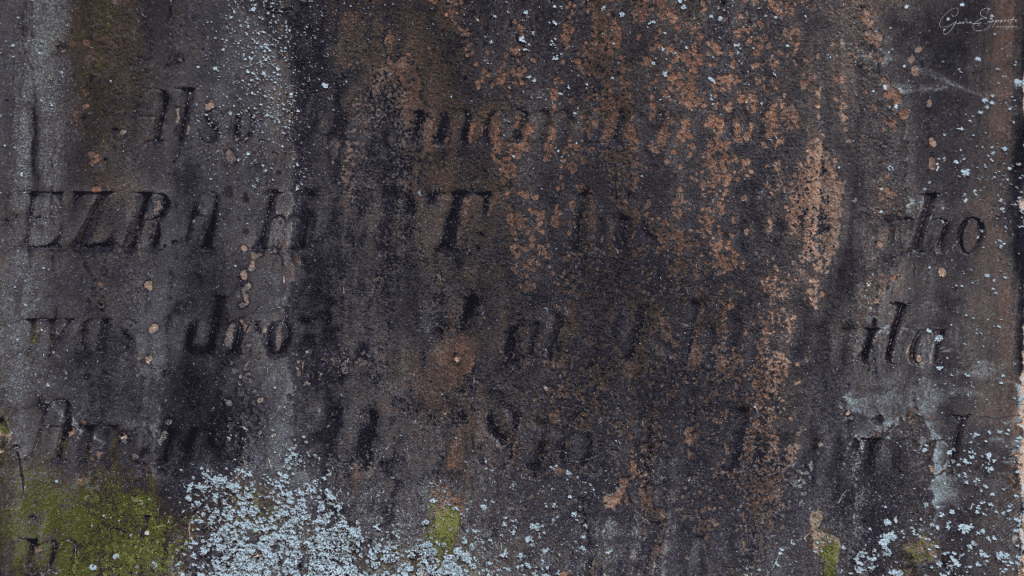

As if someone had taken a giant wedge to it, the Hart stone sits cracked in half, with only one willow out of two remaining. Carved by Brookfield resident Elijah Sikes, the stone commemorates both Gad Hart, along with his son, Ezra who preceded him in death. (Photo by the author).

Ezra Hart was born on November 24, 1797, in Avon, Hartford County, Connecticut, as the third of eight children born to Gad and Lucy Munson (Woodward) Hart. He was possibly related to fellow Brookfield settler Bliss Hart, also of Hartford County.

The exact date of Ezra’s family’s arrival in Brookfield Township is unknown, but records indicate that by the time of his sister Emeline’s birth in 1808, they were living in the area.

Worn with the passing of over a hundred seasons, the epitaph for Ezra Hart notes how he died, by being “drowned at Ashtabula August 21 1816 and buried in that town. Aged 19 years.” No record of his actual grave in Ashtabula can be found. (Photo by the author).

On August 21, 1816, at just 19 years old, Ezra met his fate when he drowned in Ashtabula. The details of the incident remain scant, but according to his headstone, carved by Elijah Sikes, his grave is empty, as he was “buried in that town”—thus making his marker a cenotaph, or a grave without a body beneath it.

In 1826, the grave gained an occupant when Ezra’s father, Gad, passed away at the age of 56.

DISCLAIMER: To preserve the headstones on this tour for future generations, please refrain from making grave rubbings or any other physical contact with the stones, including touching, leaning, or resting. Not only can these actions cause damage, but they may also destabilize the headstones.

As with any cemetery, please be respectful to those who rest here and conduct yourself in an appropriate manner. Photography is welcomed and encouraged—”Take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints.”

">

">