Braceville Cemetery in Trumbull County, Ohio, traces pioneer history with early settlers, veterans, and ties to the Taft and Barnum families.

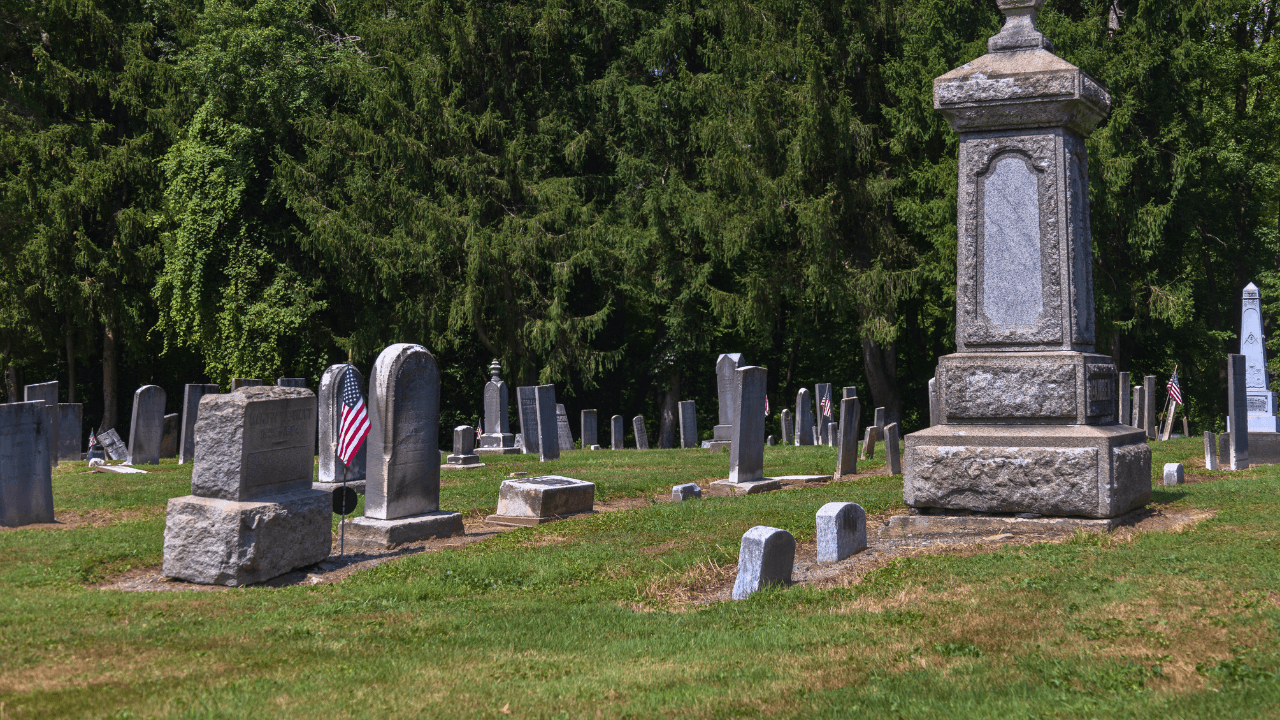

Solemn view of the oldest portion of the Braceville Center Cemetery, established in 1812 by Hervey Stow, a native of Cannan, Litchfield County, Connecticut. (Photo by the author)

A tapestry of gravestones and gravel driveways south of Braceville proper, the Braceville Center Cemetery can trace its origins to the very formation of the township. In 1812, the same year Braceville was organized, Hervey Stow, a native of Canaan, Litchfield County, Connecticut, donated what is now the oldest part of the cemetery—the northeast section—for use as a public burying ground. The following year, the yard saw its first burial with the death of Saber Lane, the 53-year-old wife of Isaac Lane Sr., also a former resident of Canaan, Connecticut.

As the community grew, so too did the cemetery, which by the eve of the Civil War had been expanded and greatly improved by Hervey’s son, Franklin, who was trained in surveying. Now under the care of township trustees, H.Z. Williams noted in his 1882 History of Trumbull and Mahoning Counties that “at present (the cemetery) is a well-kept and beautiful resting place for the dead, and many of the names of leading men and the old pioneers, who have ample mention in this history, may be found on these marble slabs. Men die but their works live forever.”

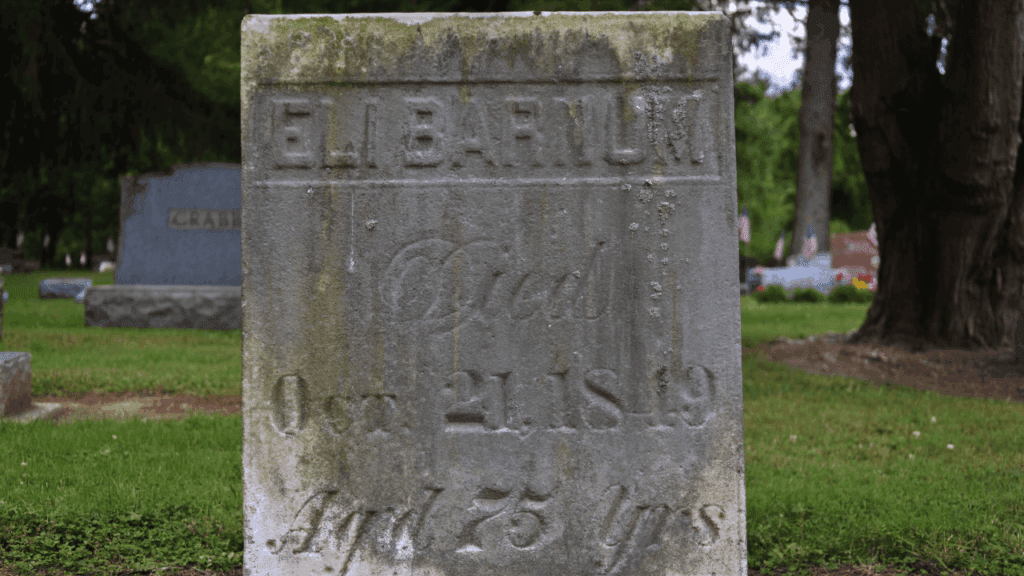

Eli Barnum

His more famous cousin may be better remembered by the general public,but Eli Barnum’s story is just as interesting. (Photo by the author)

What could the circus, socialism, and Braceville, Ohio, possibly have in common? One man—Eli Barnum—is the answer. A first cousin, four times removed, of P.T. Barnum, Eli was born on March 6, 1774, in Danbury, Fairfield County, Connecticut. He was the son of Elijah and Hannah Whitlock Barnum. While the Barnums of Fairfield County cemented their legacy in American history not through settlement in Trumbull County but through show business, Eli’s life was remarkable. It was remarkable in its own right for a settler on the Western Reserve.

Arriving in Braceville in 1811, where he settled in the northwest portion of the township, Barnum erected the community’s first flour mill along Eagle Creek. This was followed shortly by a sawmill. For 33 years, these mills served the citizens of Braceville. Then, in 1844, Barnum received an offer he could not refuse. That spring, a utopian socialist society out of Pittsburgh, inspired by the ideas of French philosopher Charles Fourier, approached him with an offer to purchase his land and buildings along Eagle Creek for $3,600. Barnum accepted, and thus the Trumbull Phalanx Corporation was born.

The new settlement, named “Phalanx” (after the French word phalanstère, meaning “communal building”), grew quickly. By August 1845, it already had 35 families and some 200 members. Though one passerby observed that “the members lived together in perfect harmony,” the community soon faced challenges. These included food shortages, financial difficulties, and recurring disease. The disease was likely caused by flooding from Eagle Creek. By 1847, the community was in decline. By 1848, after a failed attempt at rebuilding, it was abandoned. A year later, Eli Barnum passed away at the age of 75.

Jessie Taft Smith

A simple granite block marks the resting place of Braceville native and Lusitania survivor Jessie Taft Smith. (Photo by the author)

Born in Braceville Township, Trumbull County, on February 12, 1876, Jessie Taft was the last of three children of Hobart Lawrence and Mary Electa (Spaulding) Taft. She was the great-granddaughter of Aurin and Lucy Ann (Stow) Taft. They were early residents of Braceville who arrived in the area around 1812 from New Marlborough, Berkshire County, Massachusetts. On October 2, 1901, Jessie married John W. Smith, a mechanical engineer, and relocated to Chicago.

In 1911, her husband pioneered the construction of an all-steel monoplane. By January 1915, the British Admiralty, impressed with Smith’s earlier work for the French air corps in developing radial airplane engines, contracted him to assist with similar projects for their air force. This led to the establishment of the British Static Motor Company in Birmingham.

After John’s transfer overseas, Jessie returned to her father’s home in Braceville. When it was discovered that John had left vital engine blueprints with his wife, he wired £30 to Cunard agents to arrange her passage aboard the Lusitania, scheduled to depart New York on May 1, 1915.

Assigned to cabin B-20 in first class, little is known of Jessie’s daily life aboard the Lusitania. On May 7, she dined in the ship’s grand saloon before visiting the reading and writing room. Around 2 p.m., she recalled hearing “a noise” as the vessel “seemed to lift.” Some 700 yards away, the German submarine SM U-20, commanded by Walter Schwieger, had launched a single torpedo into the liner’s hull, triggering a devastating explosion. Seconds later, another blast followed—the cause still debated by historians.

This was attributed variously to stored ammunition, ignited coal dust, or a boiler explosion. Jessie hurried back to her stateroom, where she was told “not to hurry as there was no danger.” Having practiced donning her lifebelt, she made her way to the deck. She noted “the list so great” that she fell against a fellow passenger, quickly apologizing. At the starboard side, a steward thrust her into Lifeboat 13. She landed “sprawling.” After a harrowing seven hours at sea, she was taken to Queenstown (now Cobh). Four days later, on May 11, John Smith arrived from Birmingham to escort her back to England.

Although she initially appeared unaffected, Jessie soon suffered from trauma. On February 14, 1916, she was institutionalized at South Hill Nursing Home. This was reportedly from both psychological effects of the sinking and rheumatic fever. Because of her condition, John was unable to oversee the Smith Engine project, losing his Admiralty contract. After a six-month stay, Jessie and John returned to the United States. They arrived in New York on July 31, 1916.

The couple moved back to Braceville. On April 6, 1917, the U.S. formally entered World War I. Among other reasons, one was the loss of 128 Americans aboard the Lusitania. Later relocating to Philadelphia, Jessie spent her final four years there before passing away on November 1, 1928, at the age of 52. Her obituary in the Daily Local News of West Chester, Pennsylvania, described her as “a survivor of the Lusitania disaster” who died “from the shock of which she never fully recovered.” After a private service, she was brought back to Braceville. She was interred at Braceville Center Cemetery beside her parents.

DISCLAIMER:

To preserve the headstones on this tour for the generations to come, please refrain from making grave rubbings or any other physical contact with headstones, including touching, leaning, or resting. Not only can these actions damage the stones, but destabilize them. As with any cemetery, be respectful to those who rest here and appropriately conduct yourself. Photography is welcome, and encouraged: “take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints.”

">

">