Step into history with a tour of Old North Cemetery in Hubbard, Ohio. This historic graveyard holds the stories of Trumbull County’s first residents beneath its weathered headstones, offering a glimpse into the township’s early days.

DISCLAIMER:

In order to preserve the headstones on this tour for the generations to come, please refrain from making grave rubbings or any other physical contact with headstones, including touching, leaning, or resting. Not only can these actions damage the stones, but destabilize them as well. As with any cemetery, be respectful to those who rest here and conduct yourself in an appropriate manner. Photography is welcomed, and encouraged: “take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints.”

Holding the distinction of being the oldest cemetery in the township, Old North was established in 1808 on land donated by Samuel Tylee; Hubbard’s first settler. Laying atop a grassy knoll bordered by the swamplands of Yankee Creek to the west and North Main Street to the east, Old North is a picturesque setting surrounded by stately oak and maple trees. If it wasn’t for the busy road out front and the fact that it’s in Ohio, one may mistake this burying ground for one in New England. Used for burials from 1809 until 1933, while walking through, one may notice that the headstones are laid out in a haphazard manner. During the years preceding the Civil War, many cemeteries lacked distinctive, planned plots; and loved ones simply interred the departed wherever they saw fit in the cemetery. Typical of early 19th Century cemeteries in Trumbull County, many headstones in Old North are made out of brownstone, marble, and even granite, and come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Due to the hands of time, and the corrosive materials they’re made of, many of these headstones are significantly harder to read than their modern counterparts, however, the ones that can be clearly read, do tell stories.

Samuel Tylee

Located towards the middle of the cemetery to the left of the archway among a cluster of headstones stands the graves of Samuel and Anna Tylee, Hubbard’s first permanent settlers.

Born on September 1st, 1766 as the fourth out of ten children of Samuel Tylee Sr., and Hannah Emmons of Hartford, Connecticut, very little is known of Samuel Tylee Jr.’s early life, however, in about 1793, he wed Anna Dorthea Sanford, a fellow native of Hartford. Moving to Middletown, Connecticut, it was here that Tylee was introduced to Nehemiah Hubbard, one of the original shareholders of the Connecticut Land Company. In 1798, Nehemiah purchased Township 1, Range 3 on the Connecticut Western Reserve for $14,135 from Joseph Barrell and William Edwards. At 77 years old, Hubbard was too feeble to make the journey from Connecticut to Ohio to personally inspect his land holdings, so he appointed Samuel Tylee to do so for him. After a three-year-long stint surveying Hubbard’s holdings, Tylee christened the land “Hubbard Township” after his employer. Returning in 1801 with his wife, five children, and two brothers, Samuel Tylee, and his family became Hubbard’s first settlers.

Elected as the township’s first Justice of Peace in 1806, Tylee was also one of the original township trustees, and in 1808, donated a plot of land on the north end of town to be used as a cemetery. In 1818, his wife Anna passed away at 45 years old and was buried in the cemetery that he had given the land for. Remarrying to Elizabeth Ayers c. 1820, Tylee remained active in the township affairs until his death on September 1st, 1845. Buried next to his first wife at what’s now called Old North Cemetery, a plaque at the base of their plot was installed in 2003 to commentate Hubbard’s bicentennial. It gives the Tylee’s respective birth and death dates as well as Samuel’s now weather-worn epitaph: “He was the first settler in Hubbard, Trumbull County, Ohio.”

Jehiel Robbarts

Not far from Tylee’s plot is the grave of Jehiel Robbarts, who in 1809, became the first person to be interred in Old North Cemetery.

A shoemaker by trade, Robbarts arrived in Hubbard sometime before 1805 with his parents Timothy and Rhoda Robbarts from Middletown, Massachusetts. On January 16th, 1809 while carrying a pair of shoes to a customer in nearby Struthers, Robbarts attempted to cross the frozen Mahoning River when the ice broke, causing him to drown. The pair of shoes, which were left on the ice, was found later that day, which led to the recovery of his body. Brought back to Hubbard for burial, he was interred on a plot of land given to the township by Samuel Tylee the previous year for use as a cemetery, making Robbarts the first to be buried at what is now Old North Cemetery. His headstone, a simple brownstone tablet faded by the elements, makes no reference to the way he died, and simply states:

“In memory of

Jehiel Robbarts

Who departed this life

January 16th, 1809

Aged 30 years”

Rhoda Luce Gardner

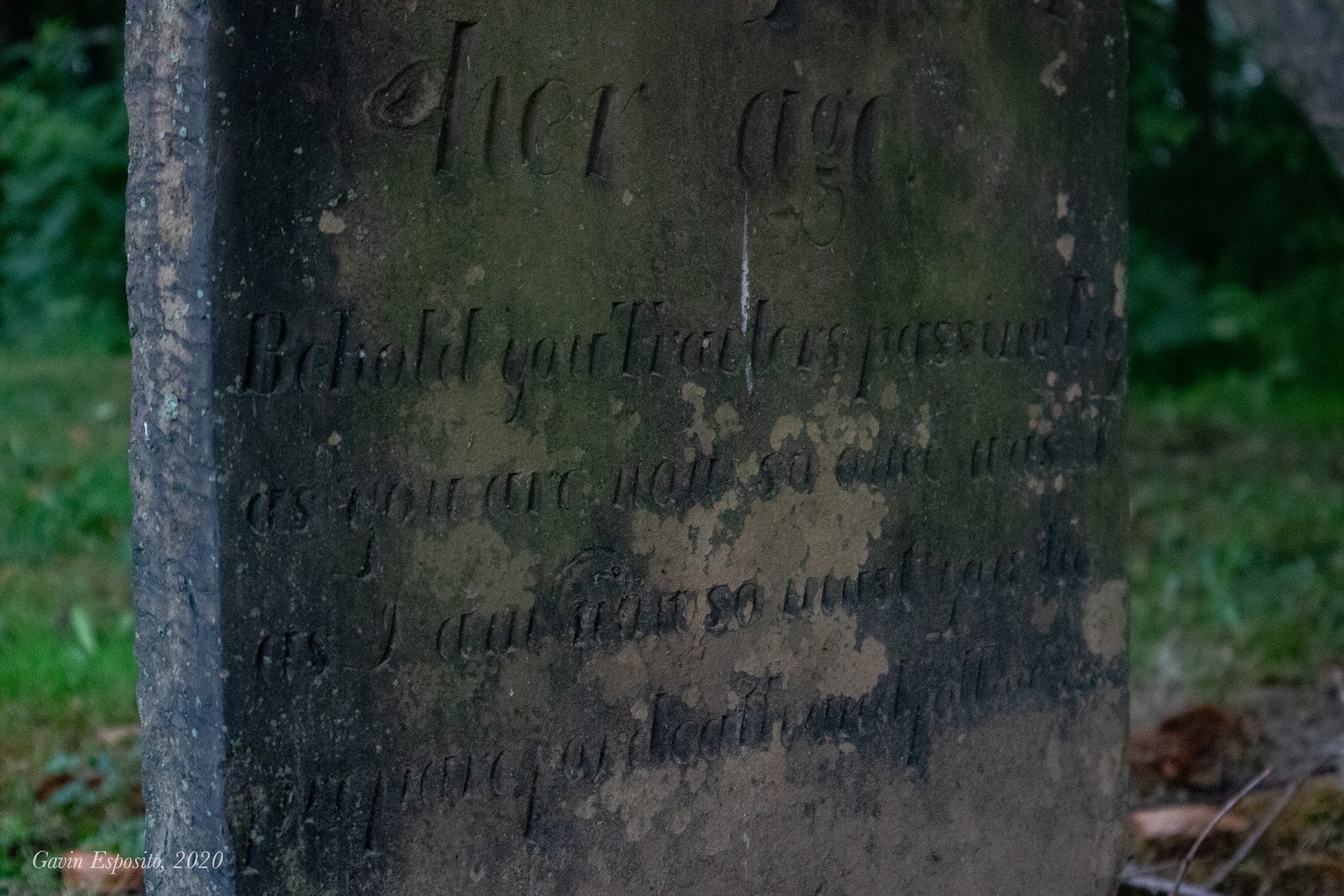

Towards the far, northern end of the cemetery is the grave of Rhoda L. Gardner, who’s marker bears a startling, if not vaguely threatening, epitaph.

“Behold you Travelers passing by

as you are now so once was I

As I am now you shall be

prepare for death and follow me”

To the modern observer, this set of verses can be quite chilling, however, 187 years ago, it was a common, if not downright cliche choice of words to have on a headstone. Thought to originate from an unknown Roman headstone inscribed with the Latin phrase “Fui quod es, eris quod sum,” or “I was what you are, you will be what I am,” as early as 1666, a variation of “as you are now so once was I…prepare for death and follow me” rhyme was used on a headstone in Perthshire, Scotland. Brought to America c. 1750, different variations of this phrase can be found on headstones up and down New England. Popular from 1750 until 1840, with some examples dating as late as 1920, this epitaph was brought to Ohio by New England settlers during the first decade of the 19th century, and used in cemeteries throughout the state. Not counting Rhoda’s marker, at least three other readable markers in Trumbull County bear some variation of this verse, with possibly more just waiting to be found or deciphered.

Born near Meadville in Colte’s Station, Crawford County, Pennsylvania on August 4th, 1801 to David and Hannah Hall Luce, the Luce family originally hailed from Sussex County, New Jersey, arriving in Western Pennsylvania around 1796. Shortly after Rhoda was born, the family relocated to Hubbard around 1802, staying here until 1820 before moving back to Pennsylvania, this time to Mercer County. Out of her 15 siblings, Rhoda was the only one to remain in Hubbard, and on January 31st, 1824, married John Gardiner, a War of 1812 veteran. On January 22nd, 1833, at the age of 32, Rhoda passed away, outlived by her husband and three children, John, Andrew, and Harriet, who when they died, were subsequently buried near Rhoda.

Frederick Cramer

Located on the far side of the cemetery near a cluster of obelisk style markers is the grave of Frederick Cramer, a former Revolutionary War captain that came to Hubbard in 1816.

Said to have been born at Wörrstadt, Oppenheim, Hessen, Germany on February 28th, 1751 to Johan Henrich Cramer and Elizabeth Kline. In 1768, at the age of 17, Cramer and his parents immigrated to the United States; landing in Philadelphia. Moving to York County, Pennsylvania, Frederick didn’t stay here long, and by 1774, was living in Sussex County, (present-day Warren County) New Jersey. That year, he married Elizabeth “Betsey” Willet of Hope, New Jersey. Like many men of his generation, when the struggle for American Independence broke out in 1775, he enlisted in the Continental Army. Signing up as a soldier in Captain James Anderson’s First Regiment of the Sussex County Militia, he worked his way up the ranks, and on June 6th, 1777, was appointed the rank of the first lieutenant: followed by a promotion to captain a year later in August 1778. Under the command of Major Samuel Westbrook, from August 9th to 29th, Cramer was in charge of 25 men at Minisink, New York. According to family legend, it is said that during some battle, Frederick fought alongside George Washington, whose horse was shot out from under him. Seeing this, Cramer jumped off of his horse and offered it to the future president, who graciously accepted it. Sadly, the legend doesn’t state which battle this supposedly occurred at, so figuring out if Washington was indeed there, is downright impossible. By 1780, Cramer retired from active duty and returned to Hope where he worked both as a farmer and shoemaker. Coming to Hubbard sometime before the 1820 census was conducted, Frederick lived the rest of his days here until passing away on June 30th, 1834 at 83 years old. His wife, who would follow him in death four years later in 1838, was buried next to him at Old North Cemetery. Through the efforts of a descendent, within the past decade, the Cramers original marker was replaced by a modern, marble one.

David Doughten

Directly behind Frederick Cramer and Elizabeth Willet’s shared marker is the headstone of David Doughten, an early settler of Hubbard who died on his way to California.

A native of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, David Doughton was born as the first out of three children to Stephen and Margeret Doughton in 1790. The elder Doughten, an ironworker by trade, served in the Revolutionary War as a gunsmith at Valley Forge, producing arms for Washington’s troops. Relocating to Trumbull County around 1804, the Doughtens settled in Hubbard, where Stephen, already trained in ironworking, took a job at Daniel Heaton’s iron furnace in Niles. Just two months after the War of 1812 broke out in August of that year, David, then 22, signed up to serve in Capt. Joshua Fobes Company of Kinsman as a private. Serving until November of that year, he returned to Hubbard and engaged in cattle raising. On June 5th, 1817, David married Maria Esther Bower, a native of Berks County, Pennsylvania who previously, before his death, had been married to Andrew Cramer–a likely relative of Frederick Cramer. The following year, the couple saw the birth of their first child named Andrew, followed by Esther Harriet in 1820. Sometime before the birth of their third child, Stephen in 1822, David erected a brick, colonial-style home at what is now 6071 Youngstown-Hubbard Road on the southwestern side of the township. Built from bricks made on-site, the home is still standing today, and holds the title of being the oldest brick home in Hubbard Township. In 1829 and 1830, the Doughtens would see the birth of two more children, Clarissia and Bower.

Unfortunately, on August 21st, 1851, at only 22 years old, Clarissia passed away. Possibly spurred by the death of his daughter and the fact all of his surviving children had grown and left home, David grew restless, and decided to set out west for California where in 1849, gold had been discovered. Leaving his wife behind, at least until he had enough money to support her out west, Doughten left Hubbard for California in 1851. Sadly, like many of the brave pioneers during this era, he would never reach his destination. On June 5th, 1852, at 61 years old, David Doughten died on his way to California. Thought to have died after being forced off the trail by local Indians or falling ill, he was interred by his comrades in an unmarked grave some 40 miles east of Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Although his mortal remains were never brought back to Hubbard, in his honor, a cenotaph, or memorial to someone buried elsewhere, was erected by his children at Old North Cemetery.

">

">