How well do you know the history of Trumbull County? Take a self guided tour of East Gustavus Cemetery and explore the final resting place of Trumbull County's early settlers

DISCLAIMER:

In order to preserve the headstones on this tour for the generations to come, please refrain from making grave rubbings or any other physical contact with headstones, including touching, leaning, or resting. Not only can these actions damage the stones, but destabilize them as well. As with any cemetery, be respectful to those who rest here and conduct yourself in an appropriate manner. Photography is welcomed, and encouraged: “take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints.”

About a mile east of the junction of State Route 193 and Gardner Barclay Road in Gustavus Township sits a small, quiet cemetery. Boarded by a farm to the east and rolling fields to the south and west, East Gustavus Cemetery was established in about 1817 for those living in the eastern portion of Gustavus Township. Inactive since the last decade of the 19th Century, the last burial in the cemetery occurred in 1892, and since then, has been closed to any new interments. Four distinct rows of headstones–many dating from before the Civil War, stick out of the ground like jagged teeth, serving as reminders to those who came before. Some have cracked, and some are leaning, however like any cemetery, the eroded headstones of East Gustavus Cemetery, although well worn, tell stories: stories of war, disease; and murder. To begin this tour, start at the northwest corner of the cemetery under the tree facing the northeast, and as you walk, look for the headstones of the people listed below.

Tucked in the far northwest corner of the cemetery under the outstretched branches of a maple tree is the seemingly brand-new headstone of East Gustavus’s most famous resident: Frances Maria Buel, who in 1832, was brutally murdered by her stepfather, Ira West Gardner.

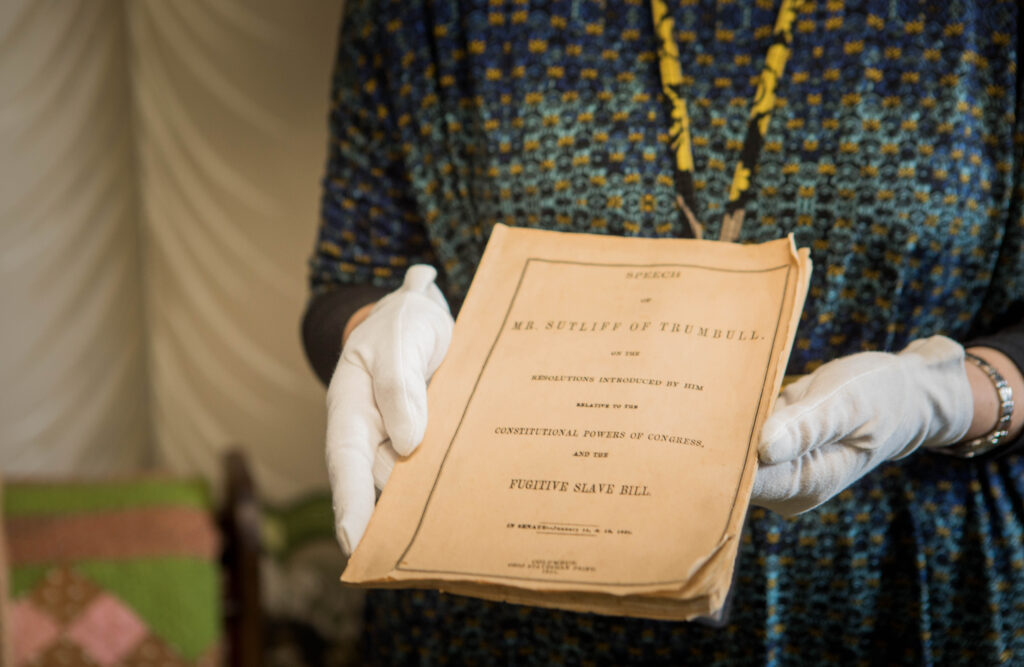

On August 8th, 1832, Trumbull County was rocked by a brutal murder. Sixteen-year-old Maria Buel was stabbed to death in broad daylight by her stepfather, Ira West Gardner in Gustavus Township. Gardner, who was born on August 4th, 1797 in Lee, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, relocated to Northeast Ohio in 1813 with his sister Sabrina and brother-in-law Josiah Smith, settling in Williamsfield, Ashtabula County. Marrying Anna Buel of Ellsworth, Trumbull County (present-day Mahoning) in 1824, Anna had a daughter from a previous relationship named Frances Maria, or Maria as she was called; born in about 1816. Gardner rented 200 acres of land from Riverius Bidwell directly west of the East Gustavus Cemetery, and like many others in Trumbull County at the time, set out to farm. In the summer of 1832, allegations of abuse started to run rampant through the small community of Gustavus—which were later confirmed to be true by Maria in a conversation with Mr. Bidwell, stating that he, Gardner, had “intercourse with her in a manner that would send him to the penitentiary.” Questioned by Riverius if the allegations were true, Gardner denied it; however, Maria’s behavior seemed to tell a different story. Frequently running away from home, often wailing about how her stepfather was “after her,” Maria’s absence from home only made Ira angrier, and to family and friends, made frequent threats of vengeance upon her return. What was later described in the court dockets as “something unpleasant” happening between the two, it seemed to reach a breaking point on the night of August 6th, when Maria left home and for the next two days, stayed at a neighbors house. In the meantime, Gardner continued to make threats against the poor girl’s life but soon stopped when persuaded by neighbors to let her come and go from home whenever she pleased. Coaxed back home on August 8th with what appeared to be a sincere promise of freedom, as well as to obtain clothes, Maria was met at the front gate by her mother and stepfather. Speaking pleasantly to Maria, as soon as her mother was out of sight, Ira produced a butcher’s knife from his pocket without warning and stabbed his stepdaughter twice. The blade, which passed through her stomach and chest, mortally wounded the poor girl, and within ten minutes of being stabbed; she passed away. Riverius Bidwell, who had been at Gardner’s house at the time of the murder, witnessed Ira stab his stepdaughter, and after wrestling the knife away from him, called for a constable. Taken into custody that evening, the next day, Gardner was transported to the Trumbull County Jail in Warren, where he would await trial.

The trial, which began in October 1832 and lasted until August 1833, found Ira West Gardner guilty of murder in the first degree. Sentenced to be executed on October 1st, 1833, his lawyers, Joshua Reed Giddings and Benjamin Wade, attempted to spare him from death by stating he was insane, pointing to erratic behavior as well as a head injury obtained in 1827 as evidence. Starting a petition which would be circulated around Trumbull County and then sent to Columbus in the hope to gain clemency, Ohio Governor Robert Lucas didn’t allow and simply rescheduled the execution for November 1st. Executed in Warren in front of a crowd of over twenty thousand spectators, with some coming from as far away as Cleveland or Pittsburgh, Ira West Gardner was the first and only man to have been publicly executed in Trumbull County. Denied a proper burial in both the Kinsman Presbyterian Cemetery as well as East Gustavus, Gardner was laid to rest in a lowly, unmarked grave on the farm of his brother in law near Williamsfield, Ashtabula County. In contrast, Maria received a grand funeral and headstone. Interred at East Gustavus Cemetery within sight of where she lived, her grave was topped with an elegant brownstone marker. Adorned with the carvings of an urn under a weeping willow–a popular motif during the 1830s, as well as the carving of a flower and drapey, her original headstone, stood over her grave for almost 150 years, however, in the 1980s, it cracked and had to be replaced. Relocated to the township hall behind a glass case, her grave was soon marked by a new, granite headstone–a close replica of the original. Seeming to glisten in the sunlight, it is a beautiful tribute for a girl who met such a terrible demise.

As with most headstones, her marker included a couplet of verses. Attributed to Phoebe Glider, a resident of Gustavus who Maria likely would have attended school with, it reads:

“Death had chilled this fair fountainere sorrow had stained it

Twas frozen in all it’s pure light

of its course

But she sleeps till the sunshine

Of heaven unchains it

To water that Eden where first

Was its source

When rising again with bright ser-

aphs attended

May she join the blest throng for-

ever high

Glad when the vile thieves murder-

ous must ever be excluded

And where pleasure abound un-

mixed with a sigh.”

The second verse, which appeared on the original headstone, isn’t included in the replacement, likely due to the fact it was rendered illegible from age.

A few short paces away from Maria Buel’s grave in the first row of headstones is the brownstone marker of Florra Scott.

Snapped unevenly in three pieces with a weed growing in between the cracks, little is known about Florra’s life aside from the fact that according to her headstone, she died on January 15th, 1842 at 29 years old. Even in its decrepit state, the ornate carvings on it can easily be made out. On the top, which has since been laid against the bottom, the likeness of big, swirling leaves is etched into the stone, while to the right of where it broke off, a diamond is present. Perhaps the most striking etching is that of a small, six-sided coffin, located to the left of the diamond. Sadly, due to the crack; only the bottom, tapered portion of it remains.

To the right of Florra Scott’s grave is a similar marker belonging to Lucy Andrews, a widow who died on February 22nd, 1840 at 67 years old.

Made out of the brownstone and featuring the same swirling leaf motif as it’s neighbor, shifting soil has caused the midsection to sink into the ground, however In a photo uploaded to FindAGrave by the user “skye” in February 2011, the headstone is seen intact, and like Scott’s headstone, features the carving of a six-sided coffin. Another, similar marker, yet again featuring the same leaf-and-coffin motif, belonging to a Lorrin Robberts, who died on October 10th, 1840 at 19 years, stands in the Logan Cemetery two miles northeast of East Gustavus. Although no carvers’ signature is present on either of the three headstones, it is without a doubt that they were made by the same mason.

Standing at Lucy Andrew’s grave looking north-east, one will see the broken marble stone of Reverius Bidwell Sr., one of the earliest settlers of Gustavus Township and the father of Riverius Bidwell Jr., Ira Gardner’s landlord.

Born in Canton, Hartford County Connecticut on August 20th, 1763 to Capt. Thomas Bidwell Esq. and Esther Orton, Reverius Sr.’s sixth-great grandparents were Stephen and Mary Hopkins, passengers of the Mayflower, and also the ancestors of President Millard Fillmore. Although his rank, company, and years of duty are unknown, Bidwell Sr. served in the Revolution, likely with the Connecticut Militia.

Marrying Phebe Roberts on September 8th, 1782, Reverius and Phebe had eight children between 1783 and 1806, with the most notable being Riverius Bidwell Jr. who in addition to being a prominent landowner, would later become the first postmaster of Gustavus as well as the Trumbull County treasurer. Reverius Sr, who came to Trumbull County with his wife and children in 1813, didn’t enjoy his new home for long, as on July 22nd, 1822, at the age of 59, he passed away. Interred at East Gustavus Cemetery, Bidwell Sr. was the second burial in the cemetery–the first being Asashel Roberts in 1817. Followed in death by his wife Phebe who died in 1837 and is buried adjacent to him, Bidwell’s grave was topped by a large slab about five feet tall inscribed with his place of birth, date of death; and age. In a 2003 photograph uploaded to FindAGrave by the member “skye,” Bidwell’s marker was intact and upright, however in a 2012 image posted on the same page by Anne Kimber: it had broken in two at the midsection, with the top portion resting behind the bottom.

Standing at Reverius Bidwell’s grave facing northeast, one will see the well-preserved headstone of Reuben and Lucus O. Roberts. Like Bidwell, Reuben hailed from Canton, Connecticut, and was an early settler of Gustavus. Lucius, his son, who served the Union during the Civil War, was a prisoner of war; and died upon his return to Gustavus.

The son of William Roberts and Margaret Merrlis, Reuben Roberts was born circa 1792 at Canton, Hartford County, Connecticut; and sometime before 1815, came to Gustavus Township with his parents. Marrying Sophia Owens on November 12th, 1816, the couple had a fairly large family quite rapidly, with seven children being born within 14 years. Working as a blacksmith, in an anecdote given in the 1882 book “History of Trumbull and Mahoning Counties” by H.Z. Williams, a neighbor of Roberts named James Bishop brought back to Gustavus with him a sprung wagon from New York state. Wagons with any kind of suspension; let alone springs, were a rarity during this era, and Bishop’s was the first of its kind in Gustavus. Reuben, who took an interest in it, was able to use his smithing skills to faithfully recreate the springs used in the wagon as a pattern. Soon, due to his skill, sprung wagons became common in the area.

Among Reuben’s seven children, three were boys. The youngest, Lucus, born in 1834, served as a private in Company F of the 6th Ohio Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War. Beyond his rank, company, and unit, little is known about Roberts’ service during the war, however, at some point, he became a prisoner of war, and was sent by the Confederates to the Andersonville Prison in Andersonville, Georgia. One of the most brutal prison camps in the South, Lucus would’ve had to contend with starvation, unsanitary, overcrowded conditions, and disease. Likely freed along with the rest of the prison in February 1865, Lucus made his way back to Ohio. Sadly, the trauma he endured at his time in Andersonville was too much, and on March 12th, 1865, died. Buried at East Gustavus Cemetery, he was outlived by his father—by only eight months. On November 10th, 1865, at the age of 73, Reuben Roberts would pass away, and was buried alongside his son who had died some months earlier.

">

">